Bogalusa, Louisiana

Bogalusa, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

Great Southern Lumber Company in Bogalusa, 1930s | |

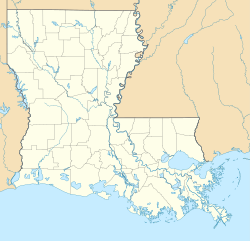

Bogalusa boundary map | |

| Coordinates: 30°46′50″N 89°51′50″W / 30.78056°N 89.86389°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Washington |

| Incorporated | July 4, 1914 |

| Area | |

• Total | 9.55 sq mi (24.74 km2) |

| • Land | 9.51 sq mi (24.62 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) |

| Elevation | 102 ft (31 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 10,659 |

| • Density | 1,121.41/sq mi (432.98/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 70427[3] |

| Area code | 985 |

| FIPS code | 22-08150 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403888[1] |

| Website | http://www.bogalusa.org |

Bogalusa (/ˌboʊɡəˈluːsə/ BOH-gə-LOO-sə) is a city in Washington Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 12,232 at the 2010 census. In the 2020 census the city reported a population of 10,659. It is the principal city of the Bogalusa Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Washington Parish and is also part of the larger New Orleans–Metairie–Hammond combined statistical area.

The name of the city derives from the Choctaw language term bogue lusa, which translates into English as "dark water[4] or "smoky water".[5] Located in an area of pine forests, in the early 20th century, this industrial city was developed as a company town, to provide worker housing and services in association with a Great Southern Lumber Company sawmill.[6] In the late 1930s, this operation was replaced with paper mills and chemical operations.

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]Incorporated in 1914, Bogalusa is one of the youngest towns in Louisiana. It was founded by Frank Henry Goodyear and Charles Waterhouse Goodyear, lumber barons of Buffalo, New York. In the early 1900s, the brothers bought hundreds of thousands of acres of virgin Longleaf pine forests in southeastern Louisiana and southwestern Mississippi for the timber and further their strategy to build railroad spurs to bring the wood to market. In 1902, they chartered the Great Southern Lumber Company (1908–38) and built the first sawmill in what became Bogalusa, a company town built to support the mill. The sawmill was the largest in the world at the time.[7][8] The Goodyear interests built the city of Bogalusa to house workers and supervisors, and associated infrastructure. They also built the Great Northern New Orleans Railroad to New Orleans to transport their lumber and products to market.[9]

The city, designed by architect Rathbone DeBuys[10] of New Orleans and built from the ground up in less than a year, had several hotels, schools, a hospital, a YMCA and YWCA, churches of all faiths, and houses for the mill workers. The town was laid out with the "Mill Town" on the south side and "Commercial Town" on the north side, altogether there were four quadrants with racially segregated neighborhoods defined by the railroad running north–south and Bogue Lusa Creek running east–west. It was called the "Magic City" in praise of its rapid construction.[11] The manager of Great Southern Lumber Company was William H. Sullivan.[12] As sawmill manager, he acted as town boss when the city was built. After Bogalusa was incorporated as a city on July 4, 1914, Sullivan was elected as mayor by white voters (blacks had been disenfranchised), and repeatedly re-elected, serving until his death on June 26, 1929.[13]

The Great Southern Lumber Company's sprawling sawmill produced up to a million board feet (2400 m3) of lumber each day. With the virgin pine forest cleared, the sawmill closed in 1938 during the Great Depression. An attempt to keep the sawmill open with California redwood proved too costly, and the mill was closed. It was replaced by the Bogalusa Paper Company (a subsidiary of Great Southern). In 1937 Bogalusa Paper Company merged with Gaylord Container Corporation; a chemical plant also run by Gaylord was built next to the mill. Crown-Zellerbach acquired Gaylord's operations in 1955. The paper mill and chemical operations continued to anchor the city's economy.

At its peak in 1960, the city had more than 21,000 residents. In 1985 Crown-Zellerbach was split up but the timber industry continued.[14]

Racial conflicts

[edit]In 1919 workers went on strike, triggering the largest labor strife at the town's Great Southern Lumber Company, the largest sawmill in the world. Company owners supported a white militia group and brought in Black strikebreakers, increasing racial tension. Events culminated in the Bogalusa sawmill killings which saw four union men killed. On August 31, 1919, Black veteran Lucius McCarty was accused of assaulting a white woman and a mob of some 1,500 people seized McCarty and shot him more than 1,000 times. The mob then dragged his corpse behind a car through the black neighborhoods before burning his body in a bonfire. [15] [16]

Civil rights era

[edit]Industrial workers of both races arrived in the company town for employment from the early 20th century onwards. Following their return from World War II, African-American veterans faced significant challenges due to racial discrimination and violence in Louisiana and the broader South. They contended with the enduring legacy of Jim Crow laws, state-enforced segregation, and systemic disenfranchisement and political exclusion, issues that had persisted since the turn of the 20th century. [17]

During the civil rights era, African-American employees at Crown Zellerbach in Bogalusa campaigned for equal employment opportunities, including access to all job positions and advancements into supervisory roles. This push for equality met resistance from white coworkers. Additionally, the African-American community advocated for the integration of public facilities in Bogalusa, particularly following the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, facing opposition from segments of the local population.[18]

The struggle against racial discrimination extended beyond black workers challenging the industrial class system. Local Ku Klux Klan members exerted their influence by intimidating civil rights activists. The situation escalated in 1964 with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, as whites intensified their opposition. Lou Major, publisher of Bogalusa Daily News, became a notable target, experiencing a cross burning in his yard by the Klan, a stark manifestation of the Klan's efforts to silence advocates for equality and justice.[19]

Determined to fight for their rights, Bob Hicks, Charles Sims, A.Z. Young, and others had taken leadership of the (all-black) Bogalusa Civic and Voters' League. On February 21, 1965, with the help of three activists from the Deacons for Defense and Justice based in Jonesboro, Louisiana, they founded the first affiliated chapter of that African-American self-defense organization. Other leaders of the Deacons were Bert Wyre, Aurilus “Reeves” Perkins, Sam Bonds, Fletcher Anderson, and others.[20] They mobilized many war veterans within the black community to provide armed security to civil rights activists and their families.[21][22] Expecting a violent summer, the State Police established an office in Bogalusa in February 1965.[21]

As explained by Seth Hague,

...the community came to embrace the militant rhetoric of the Jonesboro Deacons. Many violent conflicts ensued under this ideology and culminated in a climactic summer in 1965. Consequently, the black workers’ militancy threatened not only the power of the middle class blacks, but also the political and economic hegemony of the white power structure in Bogalusa. Except for a few noteworthy courtroom "victories" versus Crown-Zellerbach, threatening the power structure was virtually the struggle's only effect as the white power structure subsumed the militancy and rhetoric of the revolutionary Bogalusans."[21]

Two of the most notable murders of African Americans that took place in Bogalusa during the civil rights era were Oneal Moore, who was killed in 1965,[23] the first black deputy sheriff hired for the Washington Parish Sheriff's Office, and Clarence Triggs, who was killed in 1966.[24]

1970 to present

[edit]With changes in the lumber industry, through the late 20th century, after 1960, a steady decline in industrial operations, jobs, and associated population of the town occurred. By 2015, the population was estimated at slightly less than 12,000,[25] more than 40% below the high in 1960. These conditions have made it more difficult for remaining residents.

In 1995, a railroad tank car imploded at Gaylord Chemical Corporation, releasing nitrogen tetroxide and forcing the evacuation of about 3,000 people within a one-mile (1.6 km) radius. Residents say "the sky turned orange" as a result. Emergency rooms filled with about 4,000 people who complained of burning eyes, skin, and lungs. Dozens of lawsuits were filed against Gaylord Chemical and were finally settled in May 2005, with compensation checks issued to around 20,000 people affected by the accident.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit the city with winds of about 110 mph (175 km/h), downing numerous trees and power lines. Many buildings in Bogalusa were damaged from falling trees, and several were destroyed. Most of the houses, businesses, and other buildings suffered roof damage from the storm's ferocious winds. Some outlying areas of the city were without power for more than a month.

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.5 square miles (24.6 km2), of which 9.5 square miles (24.6 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km2) (0.52%) is covered by water.

Climate

[edit]According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Bogalusa has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps. The hottest temperature recorded in Bogalusa was 107 °F (41.7 °C) on June 20, 1936, while the coldest temperature recorded was 4 °F (−15.6 °C) on January 12, 1962.[26]

| Climate data for Bogalusa, Louisiana, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1930–2008 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 86 (30) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

95 (35) |

89 (32) |

86 (30) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.9 (24.4) |

79.0 (26.1) |

83.8 (28.8) |

87.3 (30.7) |

92.2 (33.4) |

95.8 (35.4) |

97.5 (36.4) |

96.8 (36.0) |

94.8 (34.9) |

89.8 (32.1) |

83.5 (28.6) |

79.2 (26.2) |

98.5 (36.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 61.3 (16.3) |

65.8 (18.8) |

72.1 (22.3) |

78.9 (26.1) |

85.4 (29.7) |

90.5 (32.5) |

92.4 (33.6) |

92.0 (33.3) |

88.8 (31.6) |

81.0 (27.2) |

70.8 (21.6) |

63.9 (17.7) |

78.6 (25.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 50.0 (10.0) |

54.1 (12.3) |

60.2 (15.7) |

66.9 (19.4) |

74.3 (23.5) |

80.3 (26.8) |

82.3 (27.9) |

82.0 (27.8) |

78.2 (25.7) |

68.8 (20.4) |

58.4 (14.7) |

52.4 (11.3) |

67.3 (19.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 38.7 (3.7) |

42.4 (5.8) |

48.3 (9.1) |

54.8 (12.7) |

63.2 (17.3) |

70.1 (21.2) |

72.1 (22.3) |

71.9 (22.2) |

67.7 (19.8) |

56.7 (13.7) |

45.9 (7.7) |

40.9 (4.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 22.3 (−5.4) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

38.9 (3.8) |

50.4 (10.2) |

60.0 (15.6) |

66.9 (19.4) |

65.7 (18.7) |

53.9 (12.2) |

38.8 (3.8) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

18.6 (−7.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 4 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

20 (−7) |

31 (−1) |

42 (6) |

48 (9) |

57 (14) |

56 (13) |

40 (4) |

27 (−3) |

21 (−6) |

6 (−14) |

4 (−16) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.14 (156) |

4.64 (118) |

5.14 (131) |

4.38 (111) |

4.51 (115) |

7.76 (197) |

6.35 (161) |

5.83 (148) |

4.72 (120) |

5.33 (135) |

4.15 (105) |

4.93 (125) |

63.88 (1,622) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.9 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 12.6 | 13.7 | 10.2 | 9.0 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 113.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Source 1: NOAA[27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2 (mean maxima/minima 1971–2000)[28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 8,245 | — | |

| 1930 | 14,029 | 70.2% | |

| 1940 | 14,604 | 4.1% | |

| 1950 | 17,798 | 21.9% | |

| 1960 | 21,423 | 20.4% | |

| 1970 | 18,412 | −14.1% | |

| 1980 | 16,976 | −7.8% | |

| 1990 | 14,280 | −15.9% | |

| 2000 | 13,365 | −6.4% | |

| 2010 | 12,232 | −8.5% | |

| 2020 | 10,659 | −12.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 4,410 | 41.37% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 5,398 | 50.64% |

| Native American | 23 | 0.22% |

| Asian | 68 | 0.64% |

| Other/Mixed | 356 | 3.34% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 404 | 3.79% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 10,659 people, 4,874 households, and 2,923 families residing in the city.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[31] of 2000, 13,365 people, 5,431 households, and 3,497 families resided in the city. The population density was 1,407.6 inhabitants per square mile (543.5/km2). The 6,300 housing units averaged 663.5 per square mile (256.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 57.18% White, 41.21% African American, 0.32% Native American, 0.39% Asian, 0.16% from other races, and 0.73% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 0.75% of the population.

Of the 5,431 households, 29.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.1% were married couples living together, 23.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.6% were not families. About 32.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 3.05.

In the city, the population was distributed as 27.4% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 21.3% from 45 to 64, and 18.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $19,261, and for a family was $24,947. Males had a median income of $26,716 versus $17,992 for females. The per capita income for the city was $11,476. About 26.1% of families and 32.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 45.1% of those under age 18 and 22.0% of those age 65 or over.

Crime

[edit]With a crime rate of 60 per one thousand residents, Bogalusa has one of the highest crime rates in America compared to all communities of all sizes- from the smallest towns to the very largest cities. One's chance of becoming a victim of either violent or property crime here is one in 17. Within Louisiana, more than 92% of the communities have a lower crime rate than Bogalusa.[32]

Economy

[edit]

Bogalusa's economy has been linked to lumbering and its byproducts since the city's founding by the Great Southern Lumber Company chartered in 1902 by the Goodyears of Buffalo, New York.[7] The sawmill was, for many years, the largest in the world. A paper mill was added in 1918.[33] By 1938, the Goodyear family's mill had clear cut all the virgin longleaf yellow pine within hundreds of miles of Bogalusa and after an unprofitable effort to import redwood from California, their sawmill operations at the Great Southern Lumber Company also ended. Bogalusa's industry then shifted to paper milling as Goodyear's sawmill passed onto Gaylord Container Corporation which was then bought by Crown Zellerbach in 1955. By the mid 1960s the mill was producing some 1300 tons of paper daily with four machines.[34] Georgia Pacific acquired the mill in 1986. Its brown paper successor owned the Bogalusa mill until 2002 when Gaylord was acquired by Temple-Inland Corporation, the area's largest employer.

The spill-over of industrial products into the Pearl River in August 2011 resulted in Federal fines of over one million dollars. The following year, 2012, Temple-Inland was acquired by International Paper headquartered in Memphis, TN and the mill came under new ownership.[35] The Bogalusa mill still operates as a corrugated fiberboard plant making boxes and shipping containers. As of 2019 the plant remains the city's largest employer with 425 people.[36] However production is much less than the 1960s with only two machines now in operation.[34]

Arts and culture

[edit]- The Robert "Bob" Hicks House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015.[37]

- The Robert Hicks Foundation was established to carry on the work for civil rights.[20] [38]

- Robert Indiana's painting "Louisiana" (1965): "Just As in the Anatomy of Man Every Nation: Must have its Hind Part: The Fair City of Bogalusa"[39][40]

- Deacons for Defense is a 2003 television movie made about the 1965 civil rights struggle in Bogalusa. Directed by Bill Duke, it stars Academy Award-winner Forest Whitaker, with Ossie Davis and Jonathan Silverman.[41]

Government

[edit]The city charter designates a mayor and a council of seven members, five of whom are elected from the respective districts and two are elected at-large, all serving four-year terms.[42]

Bogalusa is home to the 205th Engineer Battalion of the Louisiana Army National Guard, which is part of the 225th Engineer Brigade headquartered in Pineville, Louisiana, at the Louisiana National Guard Training Center Pineville.[43]

Education

[edit]Bogalusa operates its own public school system, Bogalusa City Schools, consisting of seven elementary schools, one junior high and one high school. As of 2020 there are over 3600 students enrolled and almost 230 teachers working for the district.[44]

Northshore Technical Community College is located in Bogalusa. In 1930, it was the first trade school established in the state of Louisiana, and it is now a fully accredited community college.

Media

[edit]The local weekly newspaper is the Bogalusa Daily News.[45][46] The city was home to one radio station, WBOX 920 AM & 92.9 FM[47]

Infrastructure

[edit]Highways

[edit]Bogalusa is located at the juncture of Louisiana Highways ![]() 10 running east–west and

10 running east–west and ![]() 21 running north–south. Bogalusa connects to Bush, Louisiana

21 running north–south. Bogalusa connects to Bush, Louisiana

Rail

[edit]There is no passenger rail to Bogalusa but the Bogalusa Bayou Railroad (BBAY) serves Bogalusa's International Paper plant connecting it northward with the Canadian National line in Mississippi.[48]

Air

[edit]The Bogalusa Airport, officially named the George R. Carr Memorial Air Field[49][50] is owned by the city. It is located north of the city.[51]

Police

[edit]The Police Department employs 35 officers and 12 reserves.[44]

Notable people

[edit]- Kenderick Allen, NFL defensive lineman 2003–08

- Perry Brooks (1954–2010), football defensive tackle, Washington Redskins (1977–1984), Super Bowl XVII champion

- Jacob Brumfield (born in 1965 in Bogalusa), professional baseball outfielder

- Al Clark, NFL player 1971–76

- James Crutchfield (1912–2001), barrelhouse blues piano player; raised in Bogalusa

- Melerson Guy Dunham (1904–1985) – educator, civil and women's right activist, historian

- Jack Dunlap, NSA agent accused of spying for the Soviet Union

- Rodney Foil (1934–2018), forestry researcher, educator, and administrator at Mississippi State University.

- Bob Hicks, civil rights activist. See above.

- Trumaine Johnson, Grambling and professional football player

- Yusef Komunyakaa (born in 1947 in Bogalusa), winner of 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry; born James Willie Brown, Jr.

- Skip Manning (1945–), 1976 NASCAR Winston Cup Rookie of the Year

- Janet Marion Martin (1938–2023), professor of classics at Princeton University

- John McGeever, NFL cornerback 1962–66

- Beth Mizell (born in 1952 in Bogalusa), state senator for Washington Parish

- Professor Longhair (1918–1980), funky pianist who inspired artists such as Dr. John

- Snoozer Quinn (1907–1949), pioneer of jazz guitar; raised in Bogalusa

- Jared Y. Sanders, Sr., former governor, arranged tax breaks for GSL and helped the sawmill with startup

- Jared Y. Sanders, Jr., former U.S. representative and state legislator, practiced law in Bogalusa

- E.S.G., hip hop musician

- JayDaYoungan (1998–2022), hip hop musician

- Ariel Pink, indie musician, lived in Bogalusa with his mother's family during early childhood

- Robert Benjamin Smith, former defensive end in the National Football League for the Minnesota Vikings and Dallas Cowboys

- Charlie Spikes, the "Bogalusa Bomber"; MLB player 1972–1980, New York Yankees, Cleveland Indians, Detroit Tigers, Atlanta Braves

- Clarence Triggs, unsolved murder

- Malinda Brumfield White (born 1967), member of Louisiana House of Representatives

- Dub Williams, New Mexico legislator

References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Bogalusa, Louisiana

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ "Bogalusa LA ZIP Code". zipdatamaps.com. 2023. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Leeper, Clare D'Artois (October 19, 2012). Louisiana Place Names: Popular, Unusual, and Forgotten Stories of Towns, Cities, Plantations, Bayous, and Even Some Cemeteries. LSU Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8071-4740-5.

- ^ Rony, Vera. "Bogalusa: The Economics of Tragedy". Dissent May–June 1966. p 235.

- ^ Curtis, Michael (1973). "Early Development and Operations of the Great Southern Lumber Company". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 14 (4): 347–368. JSTOR 4231349. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ a b LSU Libraries—Great Southern Lumber Company Collection Archived 2014-07-15 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2013-12-28

- ^ Barnett, James P.; Lueck, Everett W. (2020). Sawmill towns: work, community life, and industrial development in the pineywoods of Louisiana and the New South (Report). Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-257. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station. p. 68. doi:10.2737/SRS-GTR-257. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Scott, Mike (November 13, 2023). "A chic Thanksgiving for socialites in 1909 meant a trip to Bogalusa's new piney-woods hotel". NOLA. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Rosell, Thomas (June 1, 2016). "Mississippi Architects: Rathbone DeBuys (1874-1960)". Preservation in Mississippi. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Bogalusa Enterprise and American (Bogalusa, La.) 1918-19??". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "William H. Sullivan". www.southeastern.edu. Archived from the original on December 6, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Barnett, By Jim (July 17, 2017). "Great Southern Lumber's William Sullivan began aggressive reforestation near Bogalusa". Louisiana Forestry Association. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Fricker, Donna (October 25, 2007). "The Louisiana Lumber Boom, c.1880-1925" (PDF). Fricker Historic Preservation Services LLC. pp. 13–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Equal Justice Initiative 2019.

- ^ Whitaker 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Greene, Bryan. "After Victory in World War II, Black Veterans Continued the Fight for Freedom at Home". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on September 23, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Bogalusa". US Civil Rights Trail. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Against the Klan: A Newspaper Publisher in South Louisiana During the 1960s". Criminal Law and Criminal Justice Book Reviews. March 27, 2022. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "Deacons for Defense and Justice" Archived September 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Robert Hicks Foundation website

- ^ a b c Hague, Seth Hague (1997–1998). "'Niggers Ain't Gonna Run This Town': Militancy, Conflict and the Sustenance of the Hegemony in Bogalusa, Louisiana, (Outstanding History Paper)". Loyola University-New Orleans. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ "» The Deacons". Gimlet Media. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ "Civil Rights Division Oneal Moore Notice to Close File". United States Department of Justice. March 21, 2017. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Town Talk (Alexandra, LA) August 2, 1966". The Town Talk. Alexandra, Louisiana. August 2, 1966. p. 17. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Shreveport". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Bogalusa, LA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 3, 2023. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Bogalusa, 70427 Crime Rates and Crime Statistics - NeighborhoodScout". www.neighborhoodscout.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bogalusa Paper Mill". Nemeroff Law. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ a b ROBERTS III, FAIMON A. (July 5, 2019). "Why, like other small Louisiana towns, Bogalusa is slowly dying". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Amy, Jeff (December 27, 2012). "Bogalusa paper mill faces federal charges". The Advocate. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bogalusa Mill Overview" (PDF). internationalpaper.com. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Holdiness, Timothy (February 1, 2024). "Bogalusa Marks 59th Anniversary of Pivotal Civil Rights Moment at Robert "Bob" Hicks House". The Bogalusa Daily News. Archived from the original on February 8, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Bogalusa Civil Rights History". The Robert 'Bob' Hicks Foundation. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Louisiana - 1965 - Artworks-Items - Robert Indiana". Robert Indiana. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Robert Indiana". Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Deacons for Defense". IMDb. February 16, 2003. Archived from the original on December 10, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "City of Bogalusa, Louisiana / City Council". www.bogalusa.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "225th Engineer Brigade – Louisiana National Guard". Louisiana National Guard. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ a b "City of Bogalusa, Louisiana / About the City". www.bogalusa.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Bogalusa Daily News". The Daily News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Warren, Kevin (June 28, 2023). "Bogalusa Daily News going to 1-day a week". The Daily News. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Best Country Broadcasting, LLC, WBOX-FM and WBOX(AM)". Federal Communications Commission. October 26, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Bogalusa Bayou Railroad (BBAY)". Watco Companies. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "City of Bogalusa, Louisiana / Runway & Navigational Aids". www.bogalusa.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "National Weather Service : Observed Weather for past 3 Days : Bogalusa, George R Carr Memorial Air Field". w1.weather.gov. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "City of Bogalusa, Louisiana / Airport". www.bogalusa.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Bibliography

- Equal Justice Initiative (2019). "Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans". Equal Justice Initiative. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- Whitaker, Robert (2009). On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice That Remade a Nation. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307339836. - Total pages: 386

Further reading

[edit]- Honigsberg, Peter Jan (2000). Crossing Border Street: A Civil Rights Memoir. University of California Press. ISBN 0520221478.

- Keller, Larry (Summer 2009). "Klan Murder Shines Light on Bogalusa, LA". Intelligence Report.